The Number of the Beast, A Remarkable Triangular Figurate

Jan 21, 2021 7:17:18 GMT

Post by Admin on Jan 21, 2021 7:17:18 GMT

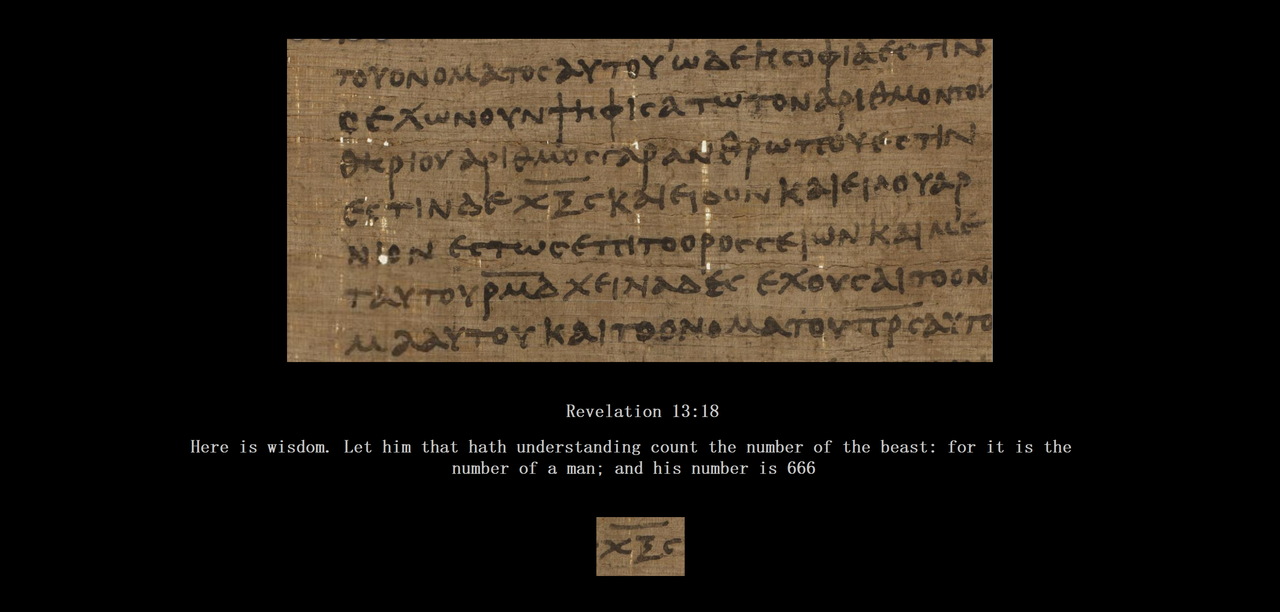

This one single number, 666, has probably inspired more conjecture through the ages than almost any other number you could think of

It's presented as part of a Biblical prophecy, in the Book of Revelation ( New Testament ), described as a name, a number, and a mark, and is said to be required to " buy " and " sell "

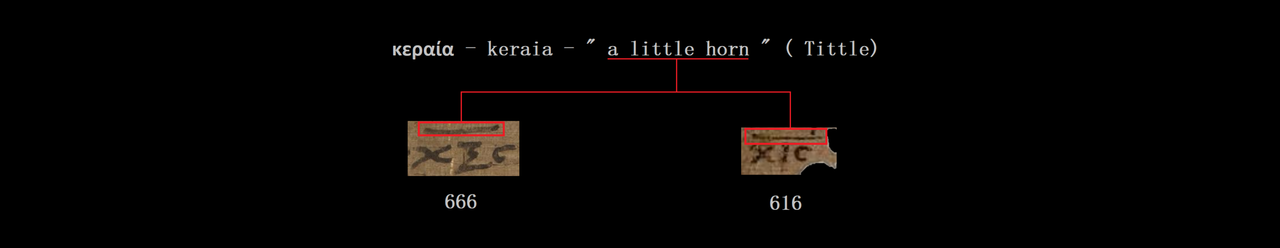

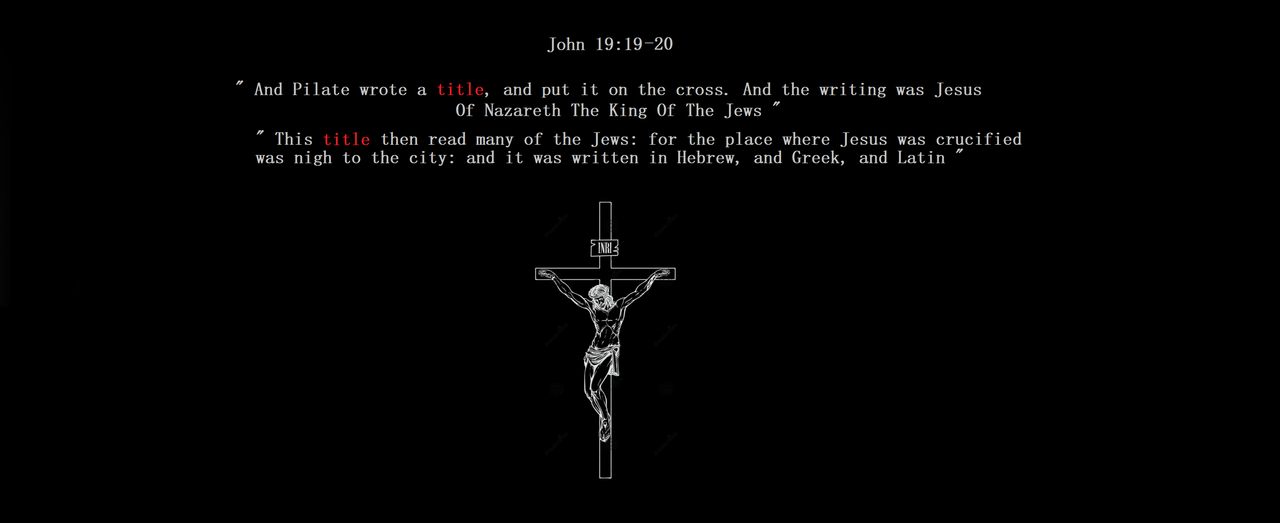

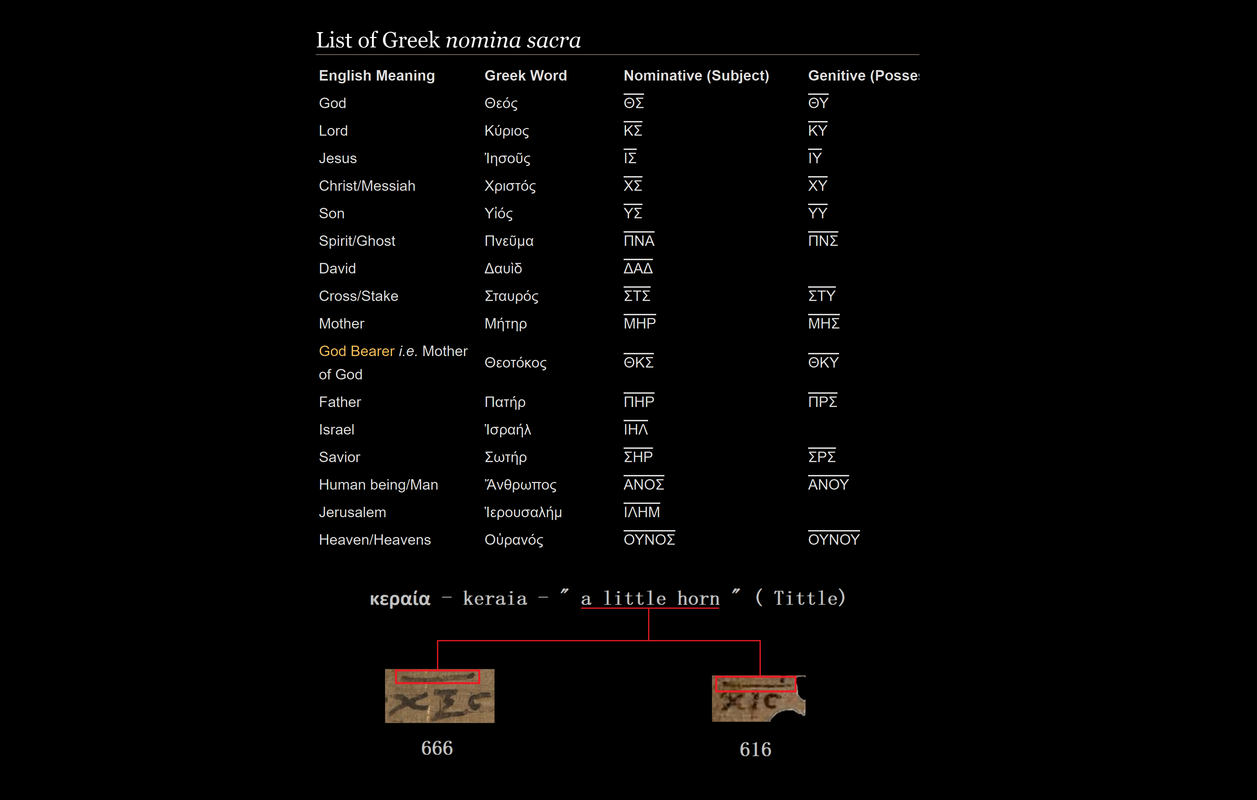

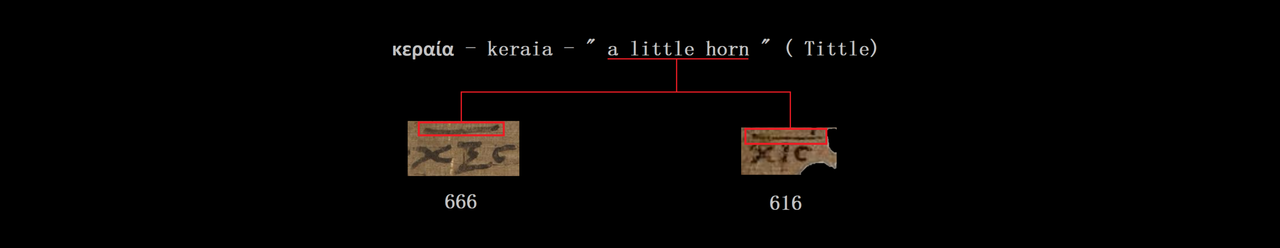

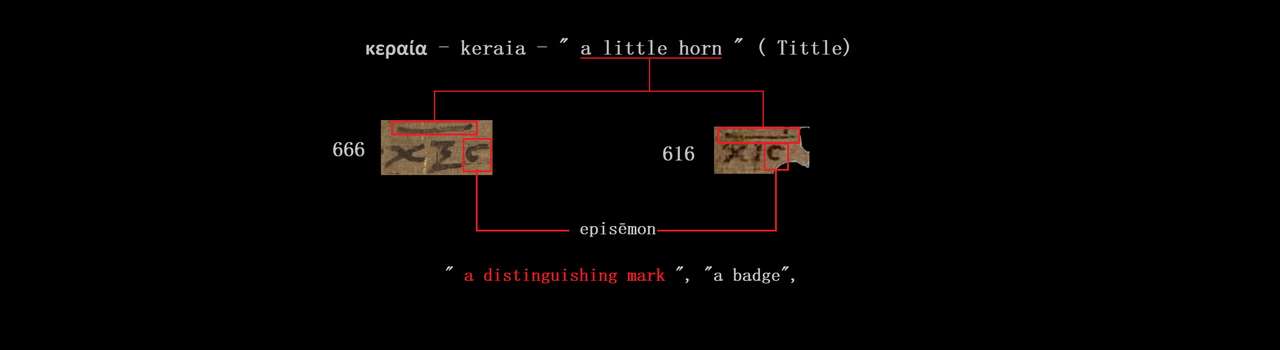

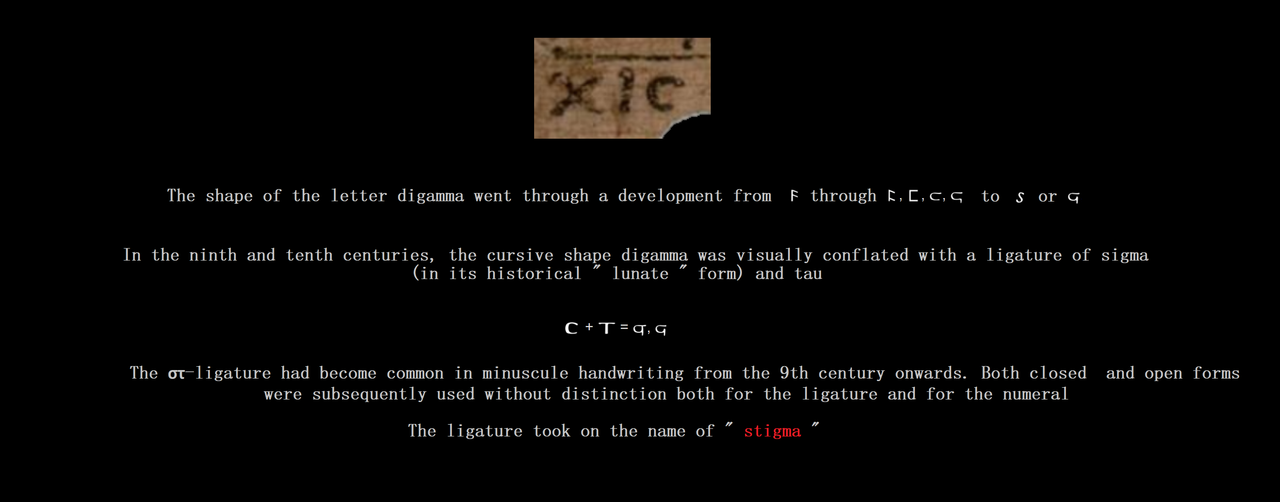

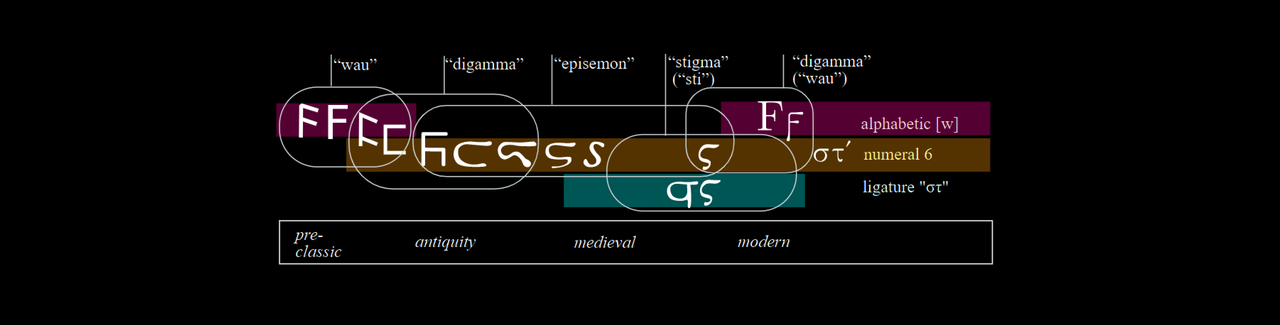

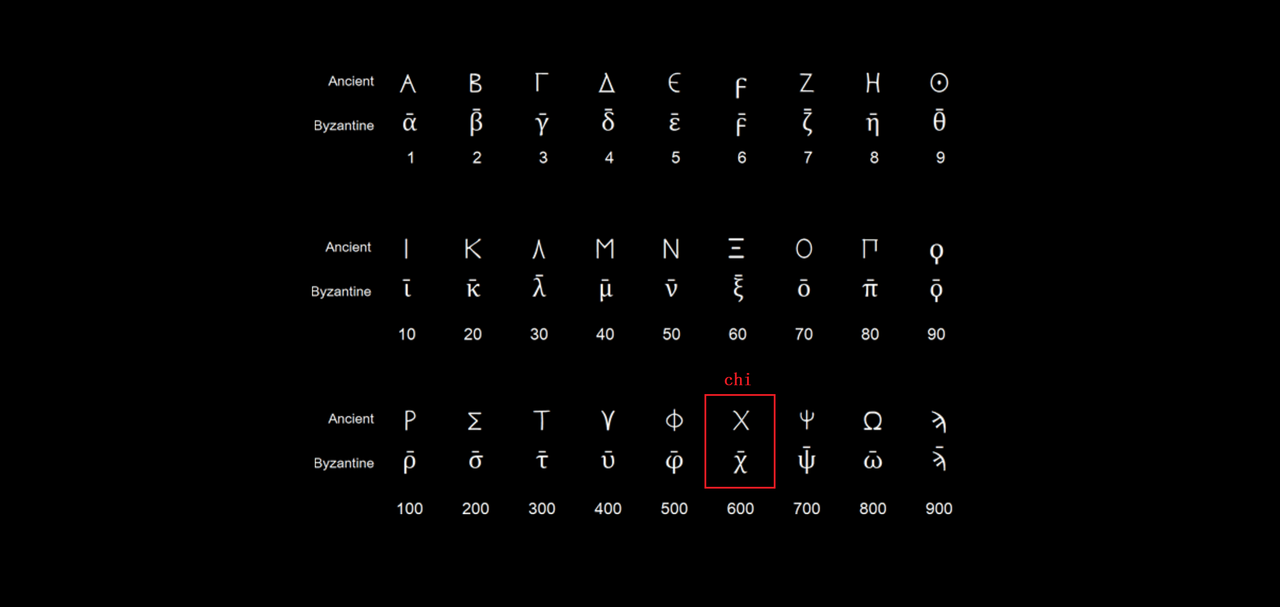

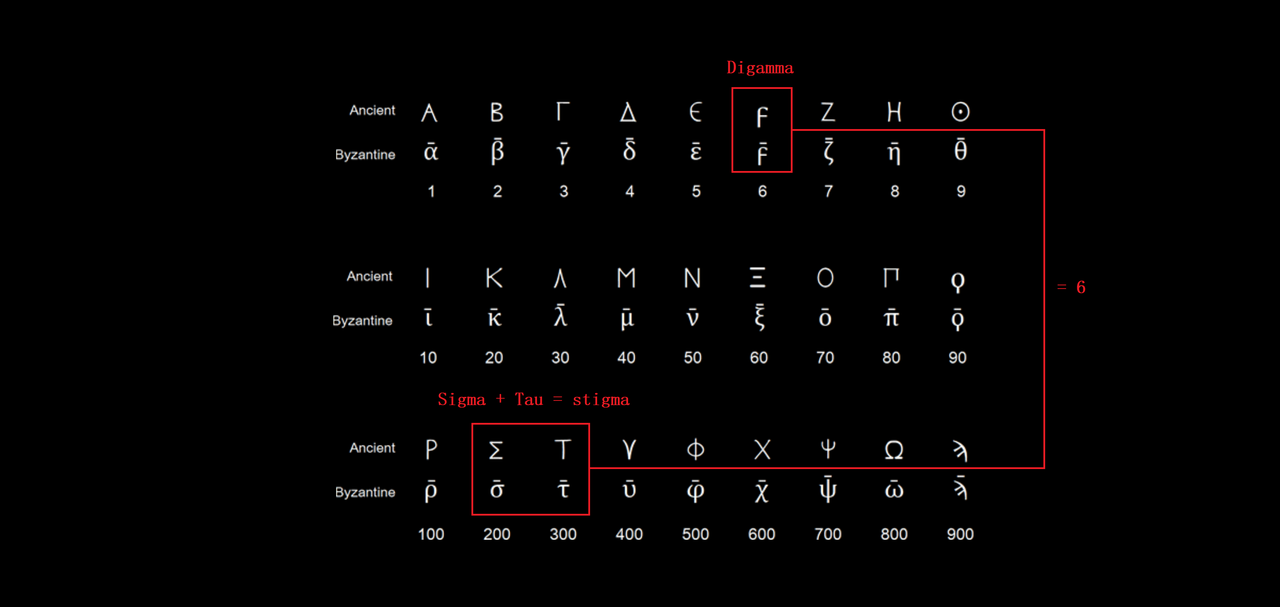

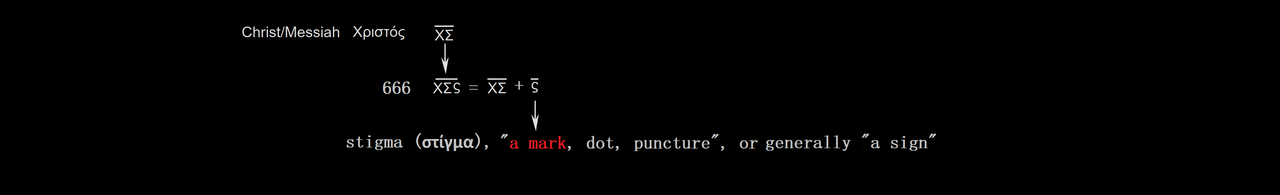

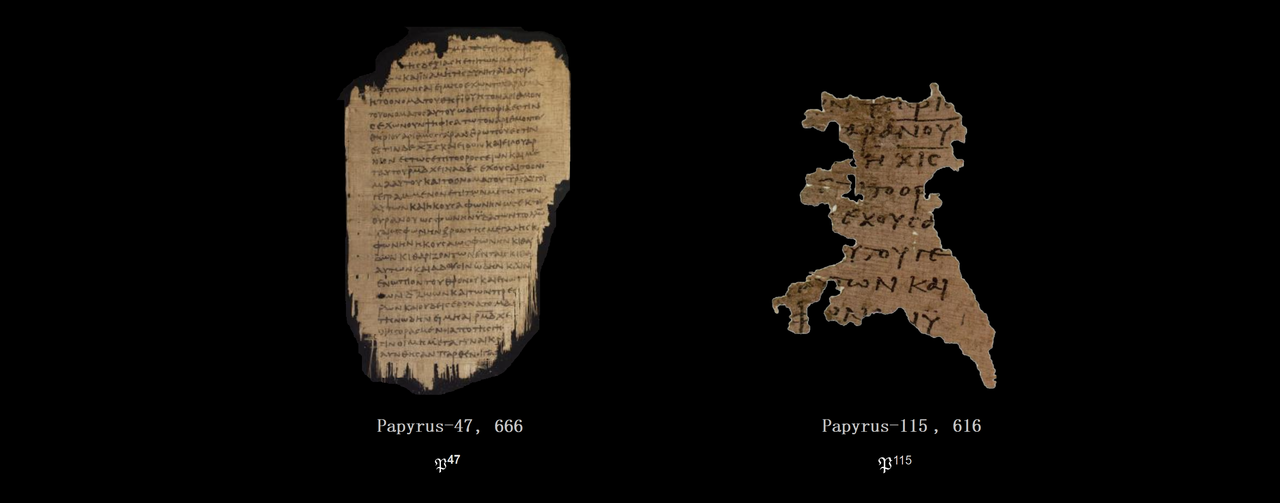

There's an alternate term, 616, other ancient sources like Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, give the number of the beast as χιϛ or χιϲ (transliterable in Arabic numerals as 616) (χιϛ), not 666, critical editions of the Greek text, such as the Novum Testamentum Graece, note 616 as a variant

In those cases, the Number of the Beast is given as as 616 (chi, iota, stigma), rather than the majority text number 666 (chi, xi, stigma)

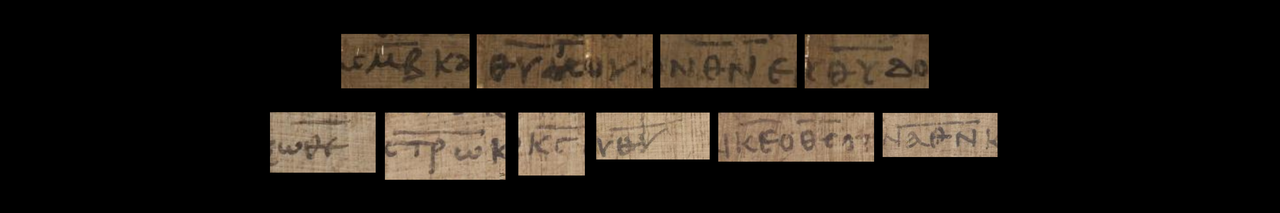

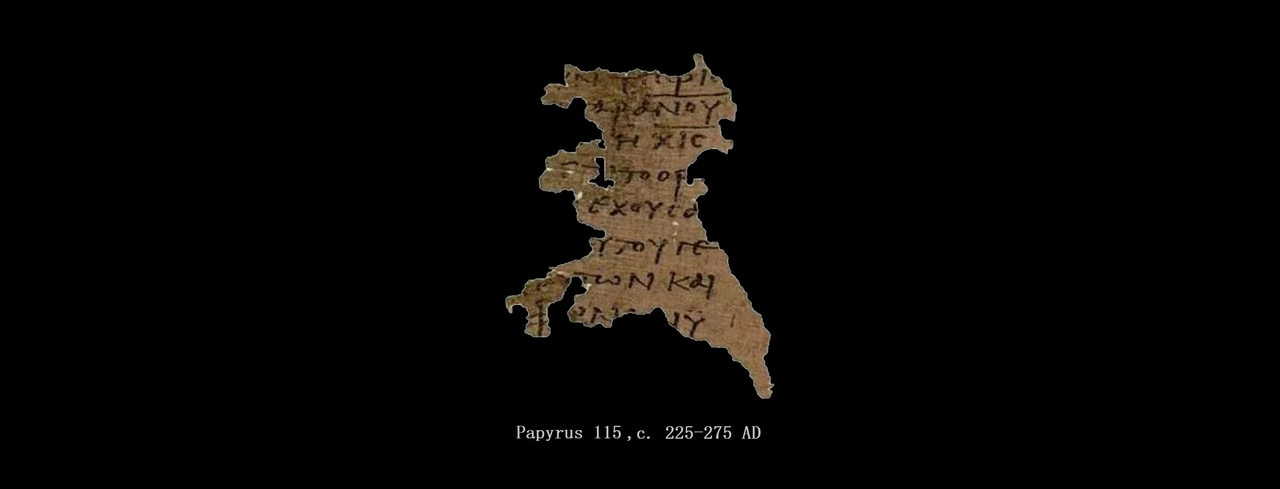

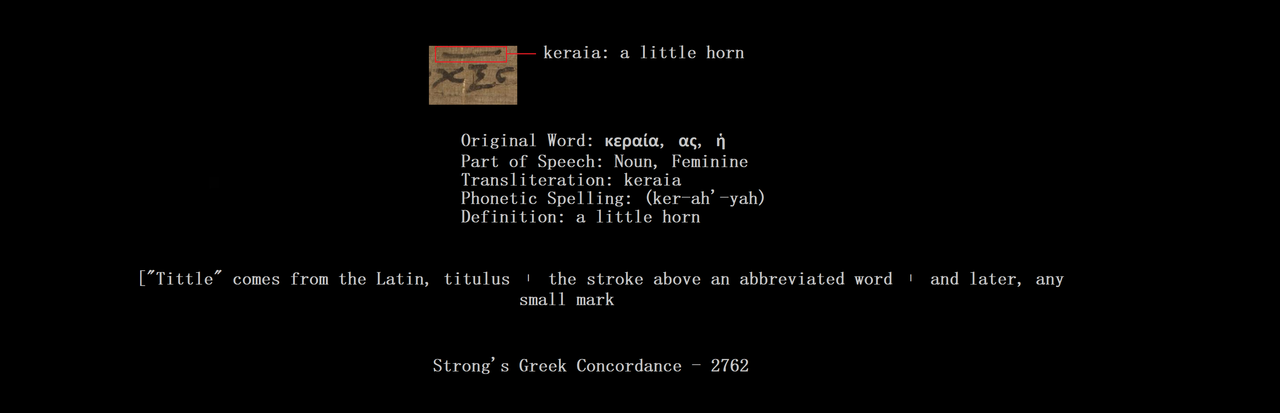

The following images are from the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts

It's presented as part of a Biblical prophecy, in the Book of Revelation ( New Testament ), described as a name, a number, and a mark, and is said to be required to " buy " and " sell "

There's an alternate term, 616, other ancient sources like Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus, give the number of the beast as χιϛ or χιϲ (transliterable in Arabic numerals as 616) (χιϛ), not 666, critical editions of the Greek text, such as the Novum Testamentum Graece, note 616 as a variant

In those cases, the Number of the Beast is given as as 616 (chi, iota, stigma), rather than the majority text number 666 (chi, xi, stigma)

The following images are from the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts

Proposed explanations for these numbers have included but are not limited to: microchip implants, tattoos, barcodes, cell phones, credit cards, social security numbers, DNA, money, Islam, Judaism, practicing Sabbath, the emperor Nero, Ronald Reagan, Barak Obama, and Donald Trump, among other politicians and public figures

However, every single one of these interpretations has failed, and as you read this thread, you'll see it's because people have not just ignored how they are actually written, but also the incredible pre-Biblical history the use of these numbers has ( Mathematical astronomy )

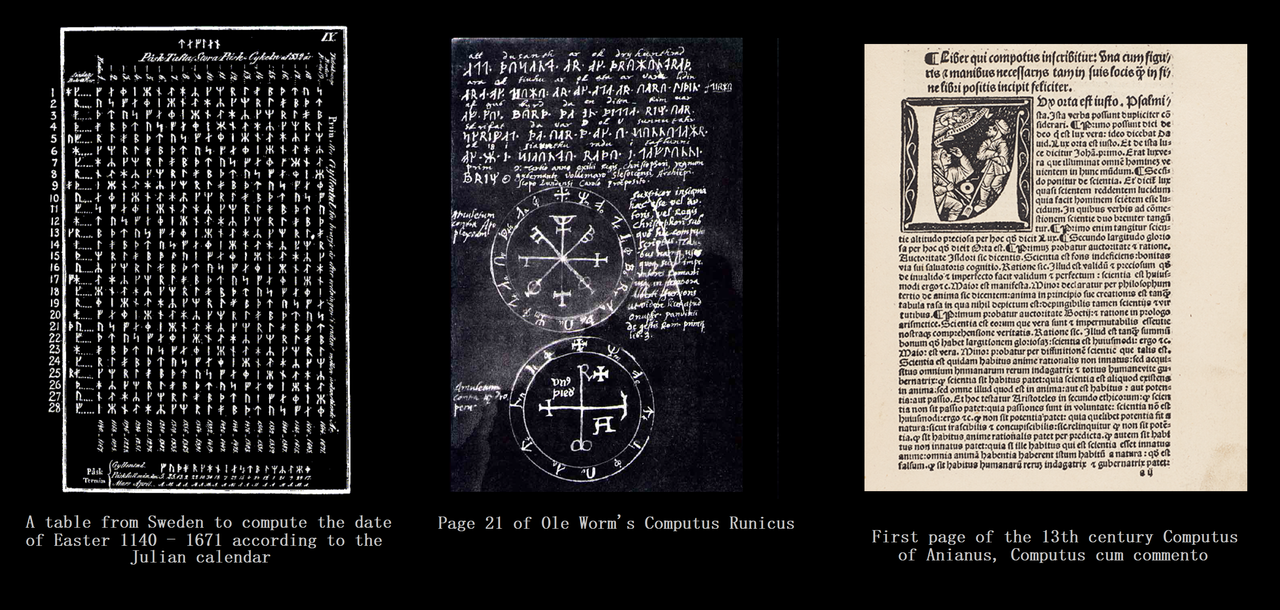

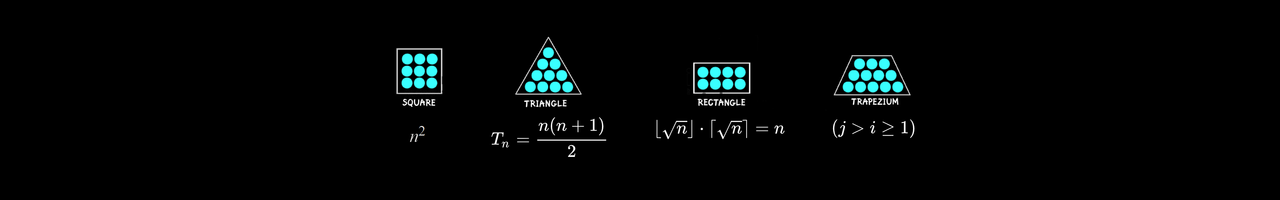

As a number, 666 is most often defined as a triangular figurate, meaning it has a rather odd connection to the history of the calculation of the date of Easter, known as Computus. Computus texts have been known to include formula for the generation of triangular figurate numbers, the Irish monk Dicuil's 9th century Computus, for example

In turn, historically, figurate numbers were used by Egyptians / Egyptian priest / Pharaohs and Mesopotamian priests / priest-kings, among others, for various types of calculations within the context of mathematical astronomy and astrometry ( Example: Egyptians were using square numbers for binary calculation several thousand years before the mathematician Leibniz, in the 1600's )

Now when it comes to the interpretation of ancient literature, whether it be the Bible, the Egyptian Rhind Papyrus, a cuneiform tablet or cylinder, or a rock inscription like the Behistun Inscription, there are typically 2 ways one can go about this

There is what's called " Exegesis " and then there is " Eisegesis "

Exegesis is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text, especially a religious text. Traditionally the term was used primarily for work with the Bible

Textual criticism investigates the history and origins of the text, but exegesis may include the study of the historical and cultural backgrounds of the author, text, and original audience. Other analyses include classification of the type of literary genres presented in the text and analysis of grammatical and syntactical features in the text itself, which include the study of the alphabets and scripts and their origins, as well as an investigation into the metrological conventions and astrometry

Exegesis can span many fields, including but not limited to: philology, philosophy, linguistics, orthography, history, and even mathematics and science

You could think of exegesis like dissecting something into it's smallest parts to see what " makes it tick "

Eisegesis, on the other hand, is when a reader imposes their biases onto the interpretation of the text, and ignores literary traditions of the period from which the text originates, and bases the interpretation on the literal word-for-word reading in English, known as " Sola Scriptura "

You've heard it said there's a right way and a wrong way to do things ?

Think " Exegesis " and " Eisegesis "

If I read Dr Seuss' book " The Cat in the Hat " and then claimed it was actually an allegorical description of how to construct a Thermal Neutron Nuclear Reactor, that would be eisegesis

One of the things you'll find religious fundamentalists commonly adhering to is a troubling habit of eisegesis

Why ?

Because they don't want cognitive dissonance, and they don't want to undermine the things they think are true by " looking too deeply ", as they're fond of saying , even though the Bible says things like

" But God hath revealed them unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God " ( 1 Corinthians 2:10 )

I've found fundamentalists take it almost as an attack on their faith, when you ask too many questions

In fact, one of the frequently heard stories from the apostates of Abrahamic religions is, paraphrased " I used to be a Christian / Jewish / insert name here, and then when I started studying the Bible, it just didn't make sense to me and the further I questioned it, the more I lost my faith in it and now I'm atheist / agnostic / insert name here "

Some may have started with a small seed of doubt, and then continued to willfully look for mounting evidence to convince themselves they were wrong, while others may have inadvertently, through various outlets, had their beliefs gradually eroded like pebbles in a stream and were left clutching nothing but a handful of sand

There are really two ways one becomes a Christian:

A. Some start by first merely claiming the Bible is " X " and they do so from peer / family pressure, perhaps argumentum ad populum ( Believing something is true because many other people do ), but their beliefs aren't stemming from their studies of the scriptures

B. Some start by first reading / studying the Bible, then come to the conclusion that they believe after some time reading / studying

Christian Apostates usually come from A, whereas B are largely atheist / agnostic at the start, so they are converts

However, where exegesis is concerned, it's handled quite differently in Judaism

Where Christian fundamentalists tend to avoid exegesis in the attempt to avoid undermining their faith, Jews do not avoid hard study, what Christian fundamentalists call " Looking too deeply "

Classically, in Judaism, when it comes to exegesis of the Torah, it is defined as having 4 " levels " , known by the acronym " PaRDeS " formed from the initials of the following four approaches:

Peshat (פְּשָׁט) – "surface" ("straight") or the literal (direct) meaning

Remez (רֶמֶז) – "hints" or the deep (allegoric: hidden or symbolic) meaning beyond just the literal sense

Derash (דְּרַשׁ) – from Hebrew darash: "inquire" ("seek") – the comparative (midrashic) meaning, as given through similar occurrences

Sod (סוֹד) (pronounced with a long O as in 'lore') – "secret" ("mystery") or the esoteric/mystical meaning, as given through inspiration or revelation

The Torah in Judaism is not a matter of " Sola Scriptura ", and this is one major difference between Christians and Jews

This brings me to the logic of " Sola Scriptura " ( By scripture alone in English )

Regardless of whether one is a Jew or a Christian, or an atheist, or even a neomaxizoomdweebie, there are several flavors of exegesis

There are people who say things like " The Bible says it, I believe it, it's God's word ! "

These types are what we can classify as " Literalists "

A literalist is someone who just reads the book and takes it as directly meaning exactly what it says, word for word

These are the types that unfortunately have a weak grasp of logic, so they believe that either " It's true " or " It's not true ", and either has to be read word-for-word as literal, or it's simply " not true "

Allegory, metaphor and figures of speech naturally present a problem for adherents to Sola Scriptura

The major flaw in that type of thinking is that it presents what's called a " false dichotomy ", which is where 2 possible answers are given to choose from, when in fact there may be a 3rd, a 4th, and even a 5th or 6th

So, ...if you happen to be a literalist, reading this, and you believe that if you suddenly somehow doubted that the accounts in the Book of Genesis, for example, actually happened as the modern Bible seems to present them, as literal word-for-word accounts, that this would mean you didn't believe the Bible is God's word...

...well, that's also not true

You can actually also believe that the accounts in Genesis are allegorical, for a variety of different reasons, or even that they are directly taken from earlier texts ( Sumerian, Egyptian, etc ), and at the same time, still hold the belief that the Bible is " God's word " ( Although the belief may actually come from a study of how literature in the antiquities was determined to be the word of a " God " or " gods " as opposed to merely taking it on good faith )

When it comes to literature from the era of the Bible, roughly 500 BC to 300 AD, as well as literature spanning all the way back to early Sumerian cities like Eridu, circa 5,000 BC, you'll find that approaching texts of this time period, literally, would get you laughed out of any serious academic circle

So when Sola Scriptura as a method of exegesis for the Bible is proposed, it should be avoided at all costs

The sad fact of it, is that the practice of Sola Scriptura is an attempt to simplify the Bible into the equivalent of a Dr Seuss book, and if we know anything about the complexities of literature circa 500 to 5,000 BC, especially anything considered a " priestly source ", we know it's capable of being ridiculously complex

This is why Biblical literalism and Sola Scriptura is a dead end road, and why the debates never seem to get settled. False dichotomies trick you into going into a debate that can never be properly resolved because literary traditions are completely ignored, which makes proper exegesis of a text impossible

It's embarrassing that academics and debaters like Dawkins, Hitchens, Dennett, et al, would even take part in such nonsensical pseudo-debates, and doubly embarrassing that so many laypeople hold them in such high regard, when the truth is that they are poorly educated in ancient literature and literary traditions

...if even educated in the matter at all

This would make them all rather ultracrepidarian, at best ( When one offers opinions outside their area of expertise )

This brings me to the area of mathematics

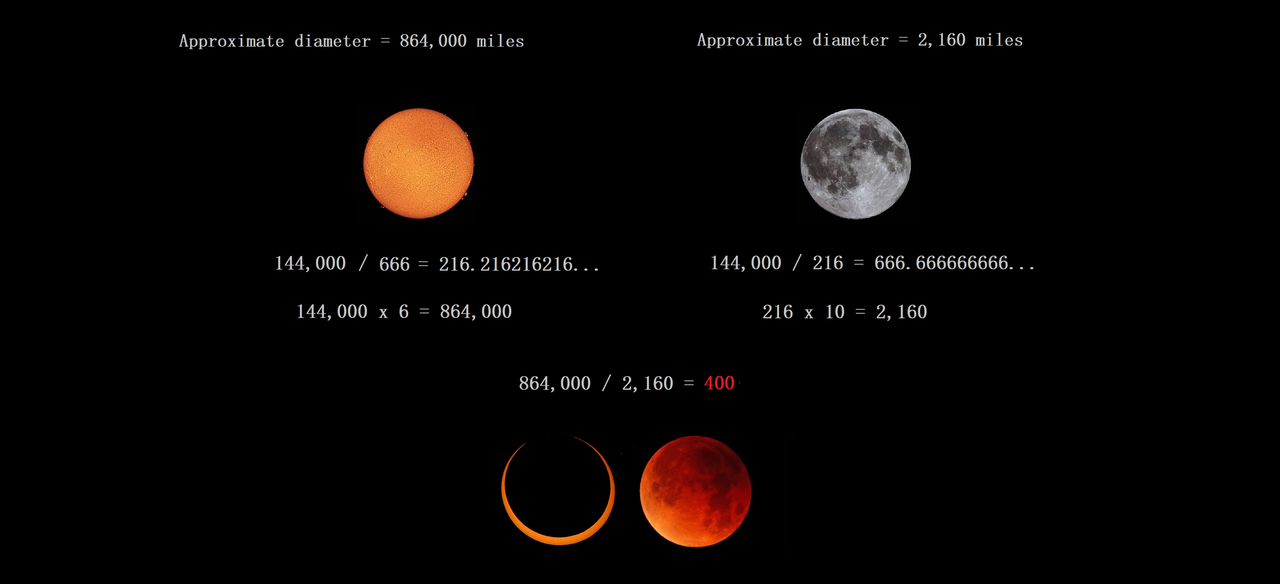

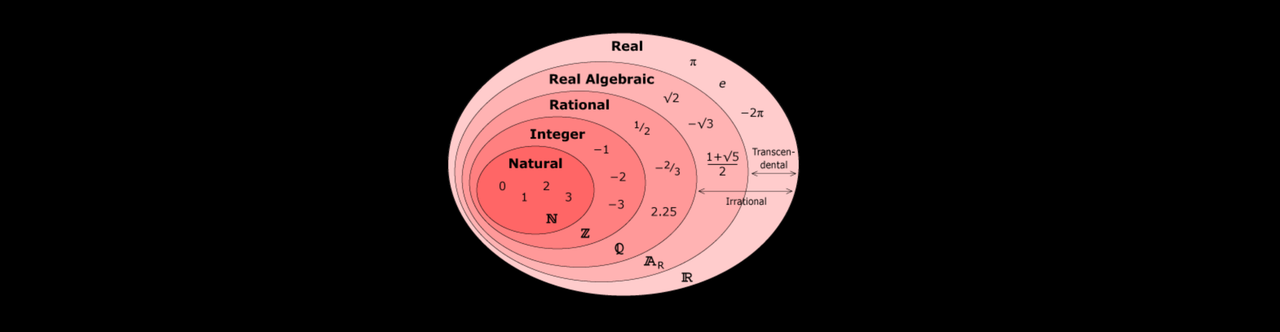

666 is like any other number, it has properties we define, and it's classified, in this case primarily as a triangular figurate. In that respect, there's nothing special about it in any way, it's just another number

One thing you may not be familiar with, is the classical use of figurate numbers like 666 in Mesopotamian and Egyptian mathematics

Most of us are at least somewhat familiar with the concept of figurate numbers, as we have all played with coins on a table top, arranging them closely in such a manner that they create various geometric shapes like triangles, squares and rectangles

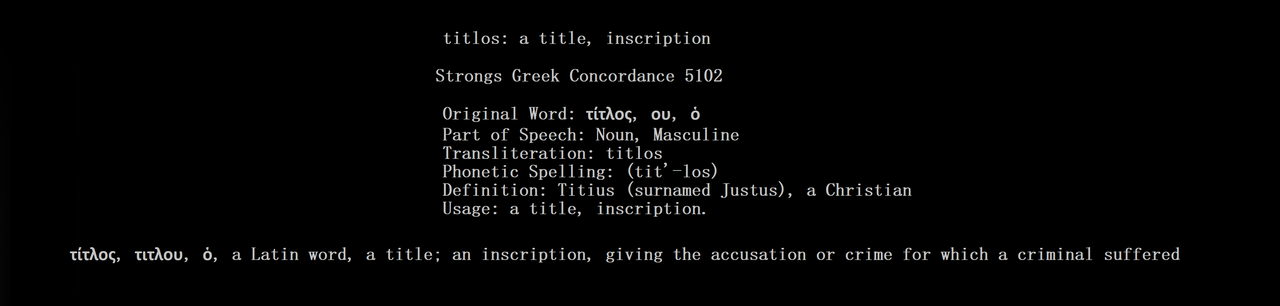

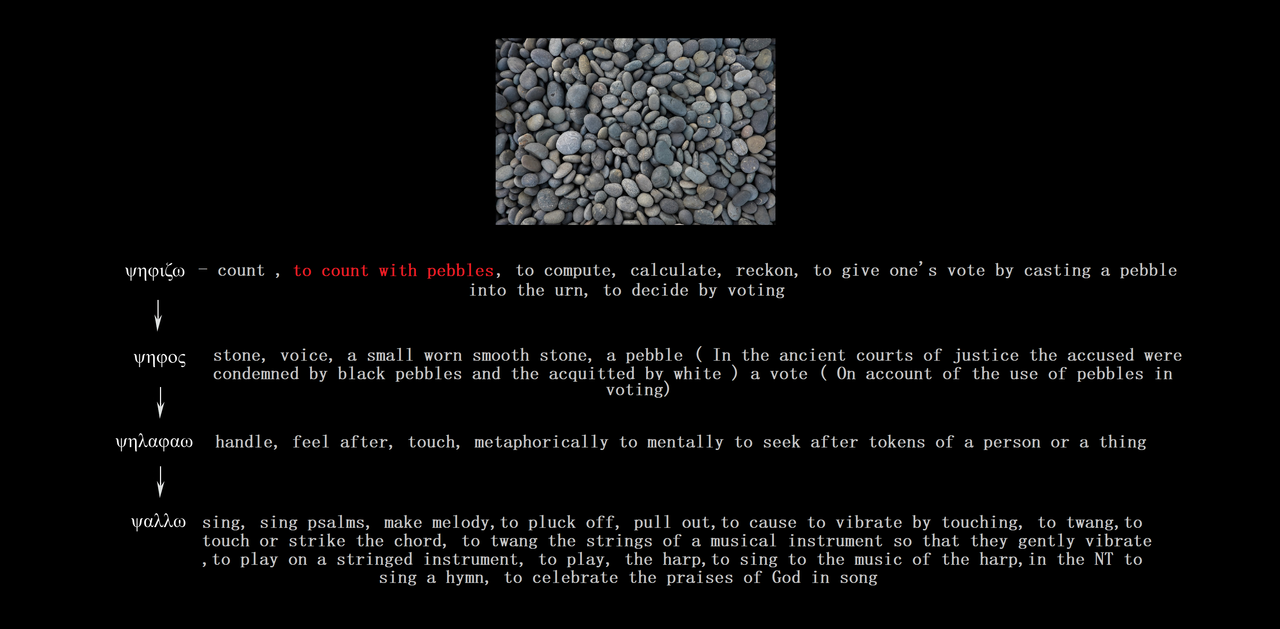

Where the Bible says " count " or " reckon " the " number of the beast ", the Greek word it uses is " psephizo ", below the Greek concordance has the etymology of the word as:

The early Greeks used round pebbles or coins arranged in patterns to learn arithmetic and geometry, which corresponds to psephos or "pebble" and "counting" in the term, but it's not quite that simple

To form the different classes of figurate numbers, you need perfectly round flat pebbles, which are relatively rare, and so coins are the preferred counter

Where pebbles are concerned- for thousands of years, democracy in action looked like a hand dropping a pebble into an urn

Smith’s “ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities ” notes that the Greeks had a syllable — konk — to represent “ The noise which the pebble made in striking against the bottom” of the metal voting urn "

A well known historical example of this is from 406 B.C., the Athenians were in a froth over the generals who won a great sea-victory over the Spartans at Arginusae but then failed to rescue survivors of wrecked ships. The citizens took a vote on whether to punish them

The wording of the proclamation, which has survived, described how it was done: “ All citizens who think the generals guilty for not having rescued the warriors who had conquered in the battle, shall drop their pebbles into the foremost urn; all who think otherwise, into the hindmost ”

Pebbles so figured in Greek democracy that a word for “ to vote ” psephizein, was based on psephos, “ pebble ” Some modern English words relating to the study of elections (psephology, psephocracy) also have a Greek " pebble " at their core etymology

Look at our English word “ballot ”. It’s from Italian, ( Little ball ) and it refers to the small balls used as counters in secret voting in places like Venice

Latin " urna " ( Urn ), in its nonvoting meanings was “ vessel of baked clay, water-jar ” also “ a vessel for the ashes of the dead ”

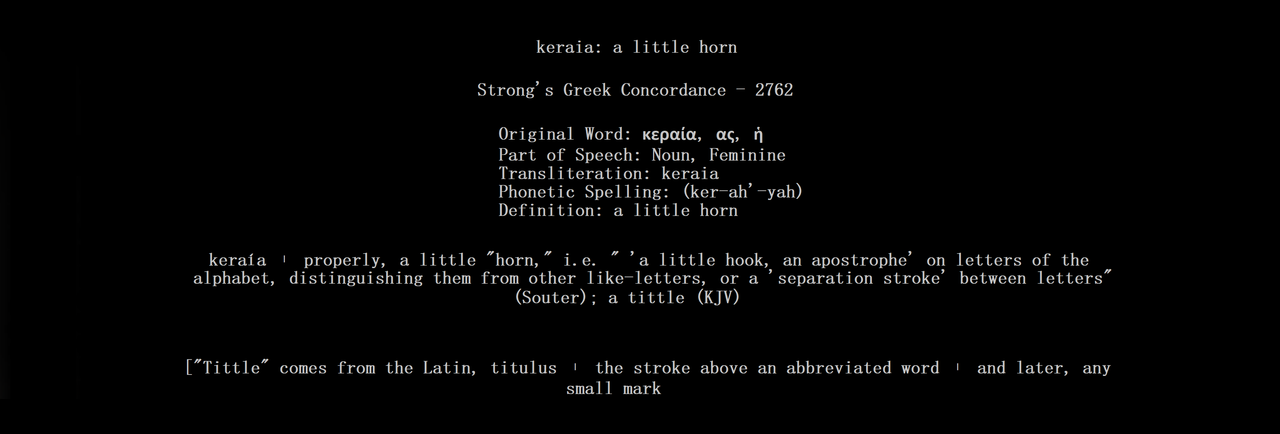

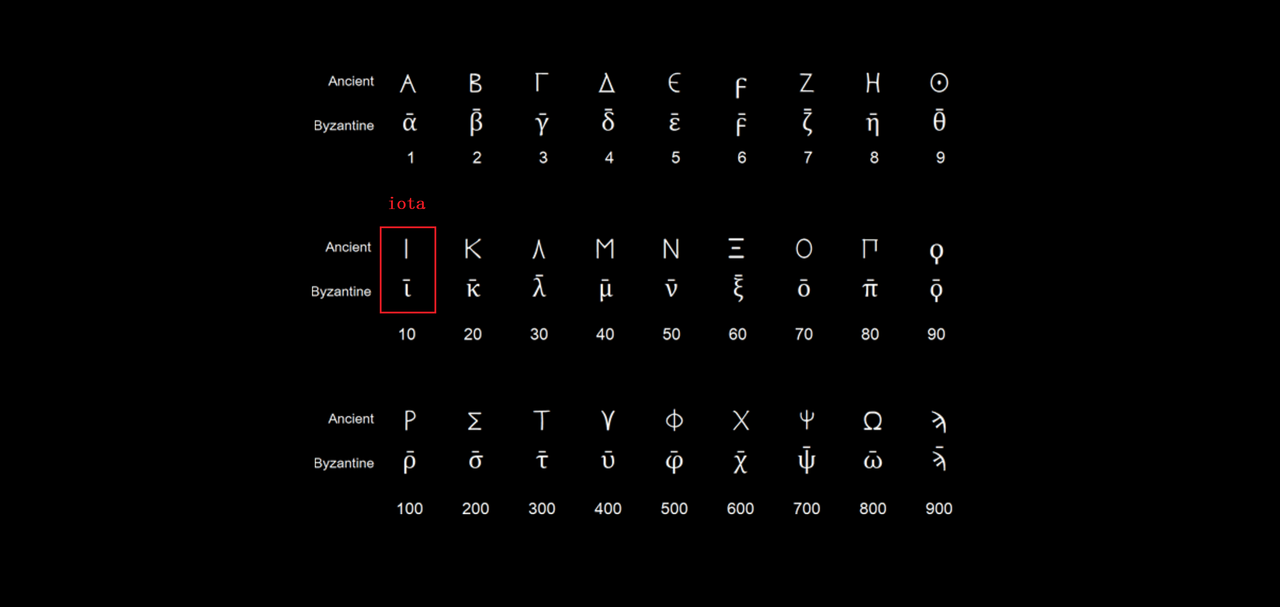

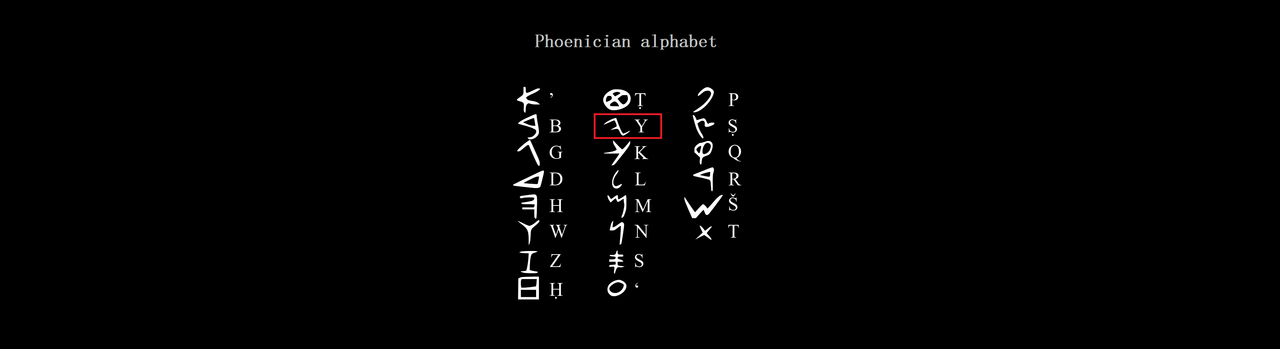

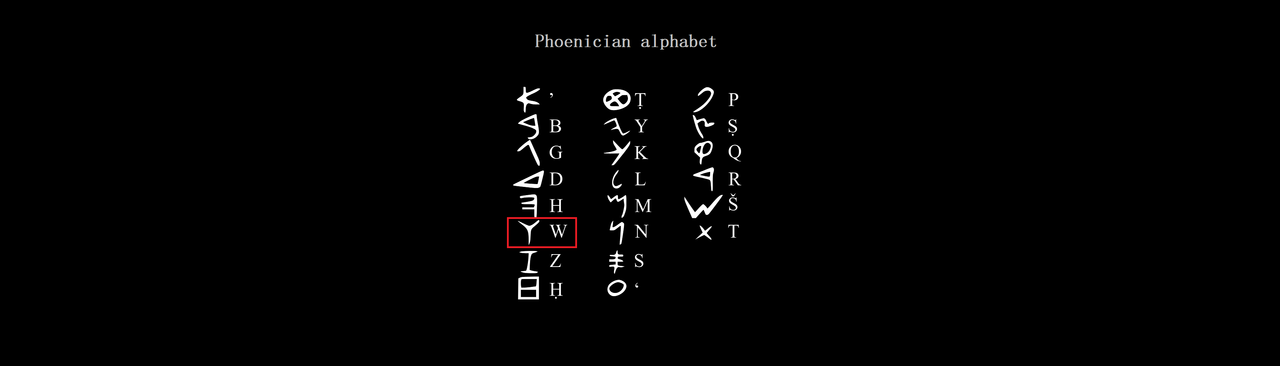

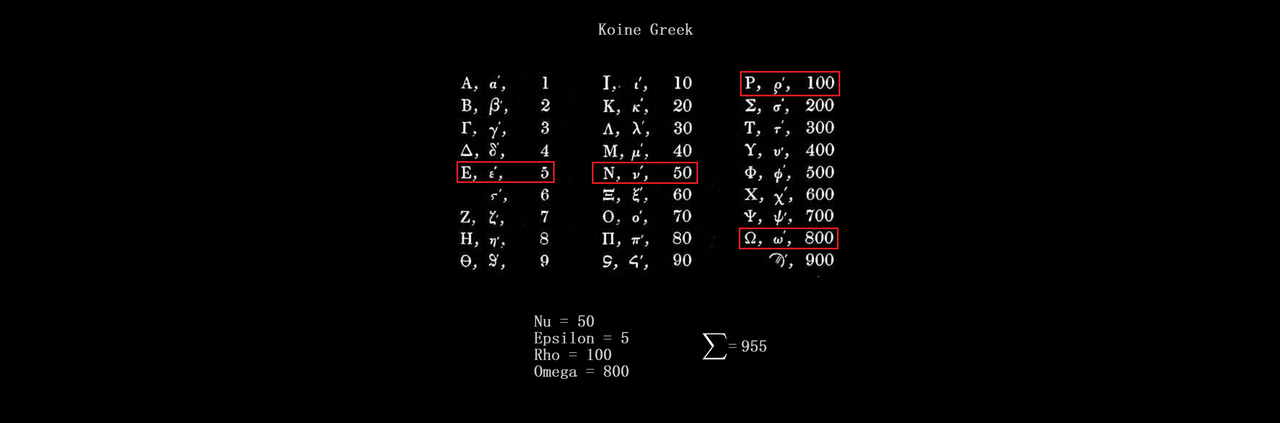

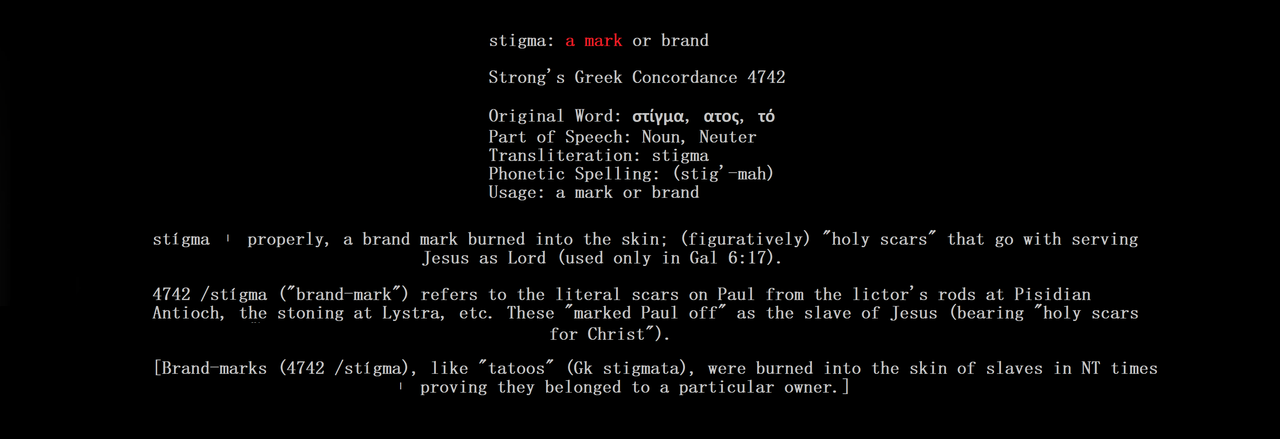

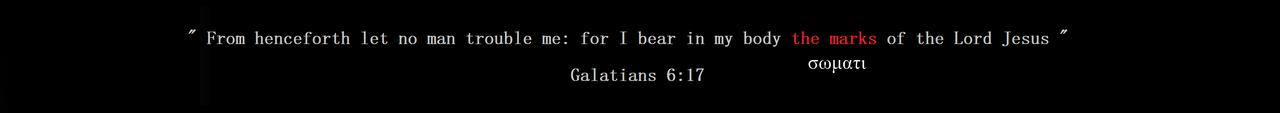

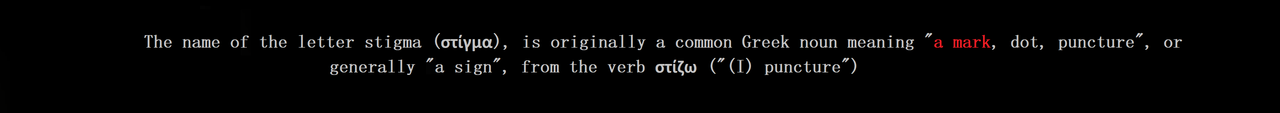

When it comes to actually writing 666 or 616 in Greek ( Or Hebrew ), this requires adding up the numerical value of the letters ( Technically called " Graphemes " )

Prior to the advent of the Hindu-Arabic numerals 0-9, graphemes of a script were used to write numbers, this is technically known as " polysemy " ( When something written has multiple possible meanings ) and is common with ancient languages

It's distinctly different from " numerology " in that it's a standard convention of written mathematics from the period, whereas numerology is something done via a pre-existing convention of writing

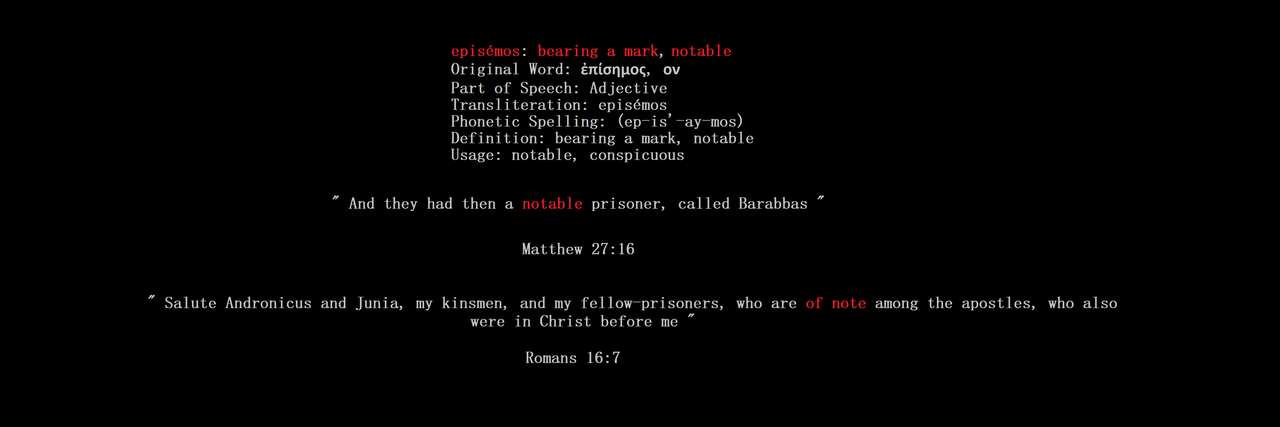

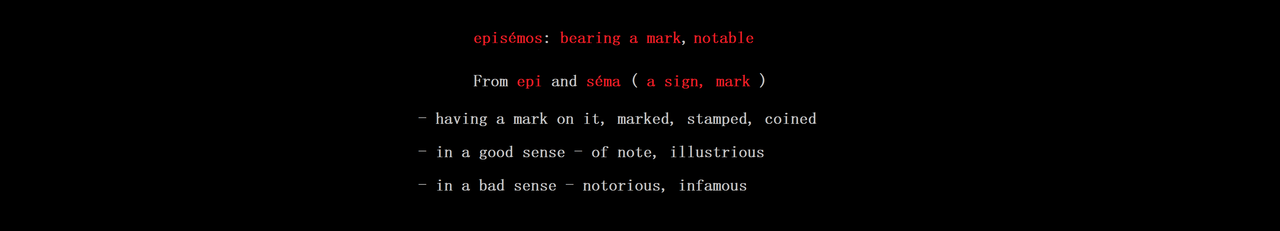

Isopsephy , ἴσος isos meaning "equal" and ψῆφος psephos meaning "pebble") or isopsephism is the practice of adding up the number values of the letters in a word to form a single number. The total number is then used as a metaphorical bridge ( What is known as " Gematria " ) to other words evaluating the equal number, which satisfies isos or "equal" in the term

" Gematria " technically falls under the category of " Numerology " , yet in order to understand why numbers were considered " sacred " in the antiquities, one must delve deeply into priestly literature and tradition

Where a modern numerologist might say something nonsensical like " 7 is God's number because it's the number of completion ", a piece of literature from the corpus of a lunar priest might say something like

So you can see, the difference is quite large, in that a modern numerologist's claims have nothing to do with the way mathematics were handled by priests in the antiquities

In the above colophon warning, it says that the table of data from astronomical observations ( Ephemeris ) is both sacred and protected ( By the gods ) and that any attempts to interpret it without their guidance as classical tutelary deities, would result in what is considered " false prophecy "

In this case, it would result in a person incorrectly predicting a phenomenon like New Moon, an eclipse, or a conjunction / syzygy

This is easily understood

A person in modern times looking at an ephemeris, and trying to predict something like new moon, without being educated in what an ephemeris is, or how to properly analyze it for periodicity, would indeed falsely predict it's timing

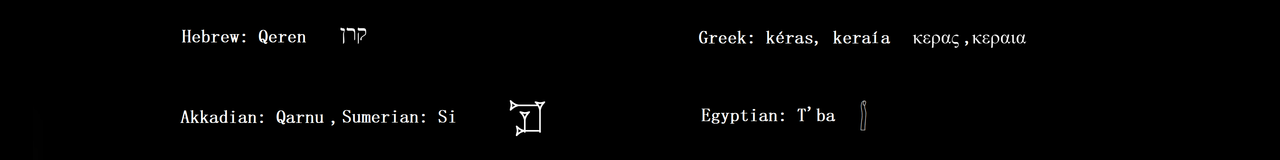

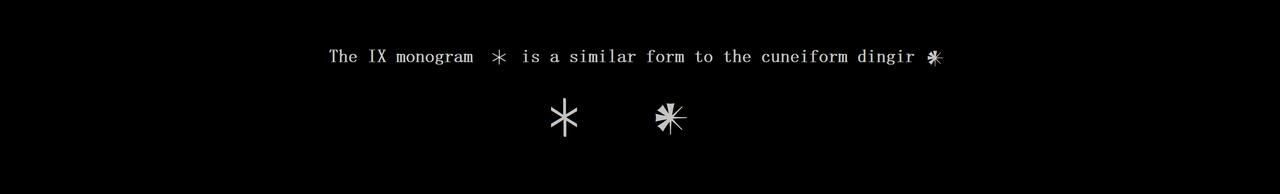

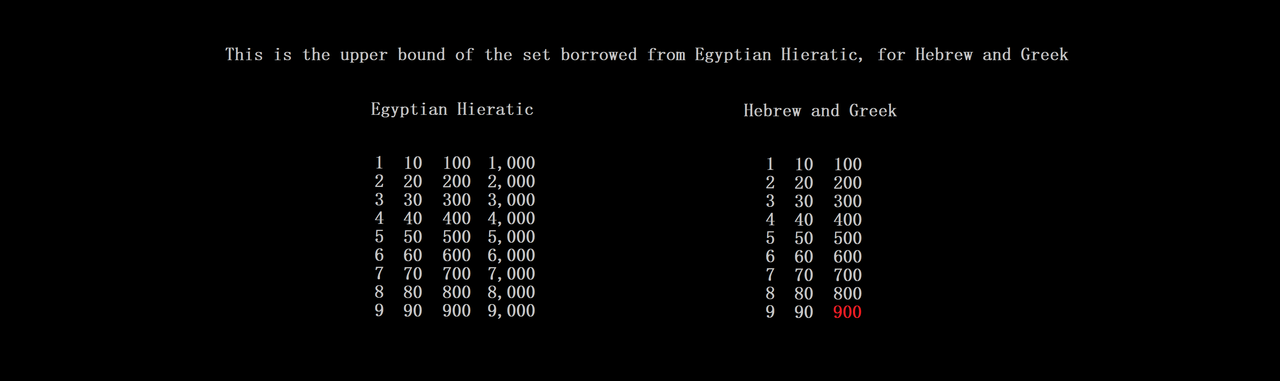

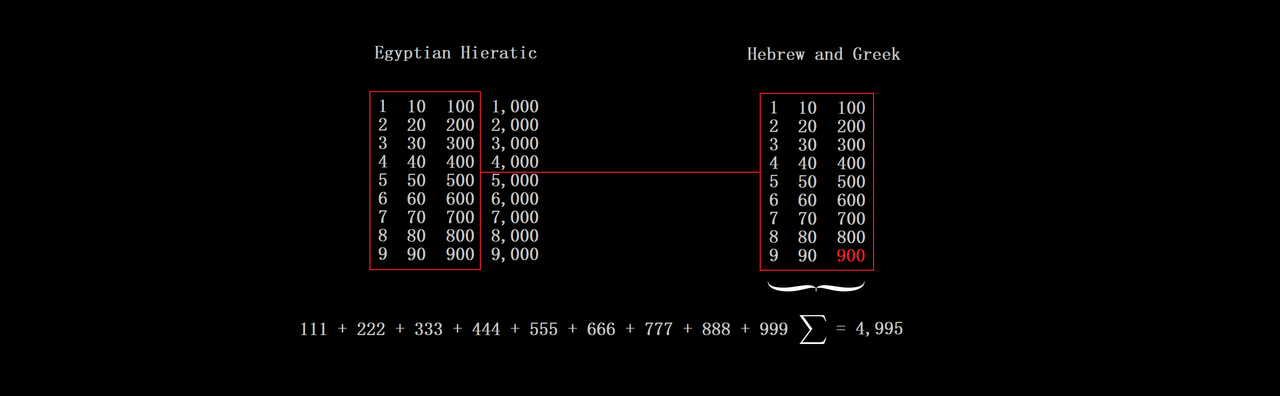

When it comes to the polysemic Hebrew and Greek alphabets, the numerical " structure " is easily shown to have been borrowed from the Egyptian priestly script, Hieratic

In turn, this base belonged to a body of astronomy calculations using a set of " repunits "

Modern numerologists have missed that the sum of the alphabets used to write the Bible is the sum of the repunits {111-999} they play around with

Modern numerologists have missed that the sum of the alphabets used to write the Bible is the sum of the repunits {111-999} they play around with

In this case, among the repunits, only 666 is triangular

------------------

Now we have to ask: " Is mathematics the same as numerology ? "

Numerologists would say " Yes ! " and mathematicians " No ! "

Various types of numerology don't " use " mathematics so much as they invoke mathematics, but pure math itself pre-dates the advent of numerology, by quite some time, as far as what we know from ancient cuneiform texts concerning metrology / astrometry / mathematics

If numerology could be reliably used to make predictions like pure math, then it might qualify, but we can reasonably say they are not the same

" Invoking " mathematical concepts is not the same as " using " mathematics, as " using " mathematics has an end, a purpose and an outcome, whereas numerology is just a stab in the dark

We should also ask " Is math divine ? "

This question is not so easy to answer, even though once again:

Numerologists would say " Yes ! " and mathematicians " No ! "

Why this is not so easy to answer, is that in the antiquities, mathematics associated with Lunar, Solar, and Planetary gods, was indeed considered " sacred " or " divine "

Specifically, the mathematics involved with calculations of things like eclipse cycles, new moons, conjunctions and syzygies, etc, what are technically called

" Omen " . Omen texts include the Enuma Anu Enlil series

The tables of astrometric data taken from the observation of priests, were also considered divine

This is not a matter of " numerology ", this is a hard fact of pre-Biblical cuneiform and Egyptian literature, ( Not shockingly, I've been run off more than a few forums / chats for attempting to discuss it )

This requires in turn requires an in-depth look at what was considered " divine " and exactly how that determination was made to begin with

" Divinity " in modern times has no objective definition, especially among the laypeople, regardless of religious beliefs

In the antiquities, however, there are clues in historical literature we can use to better understand how they saw " divinity "

You see, in order to answer the question " Is math divine ? ", we have to first address the concept of " divinity "

More accurately, we're asking " Was math divine ? " ( In the antiquities )

If the answer turns out to be " yes ", then we have to look at what lead to this determination

==============

Notes